Since I’m still working on background chapters for my dissertation and hence currently do not have to share any research updates, I’m going to focus today’s blog post on my teaching duties. More specifically, I’ll try to convince you that grading sheets are a useful tool for making your own grading process more structured and objective, as well as for providing students with valuable feedback.

The Problem: Unstructured and Opaque Grading

But before we discuss grading sheets as a possible solution, let us first take a look at the problem setting.

In academia, students have to take a certain number of courses before they can graduate, including lectures, seminars, and practical courses. Typically, students receive a grade for each of their courses. This grade can be based on a written exam, an oral exam, a seminar paper, a presentation, programming exercises, and many other deliverables. As discussed in an earlier blog post about constructive alignment, the type of examination should be based on the learning targets for the respective course.

As a lecturer, one is now faced with the task to give a grade to each student, which should reflect to which extent they have reached the learning targets. In a written exam, this is usually relatively straightforward and reasonably objective – usually, you first come up with a sample solution for the exercises and then check how close the student’s responses are to the desired ones. Structured exercises like multiple choice are very easy to evaluate (just check whether the right choices have been selected), but also short free text exercises can be graded quite easily by looking for certain keywords that need to be mentioned.

If we have however other forms of examinations such as seminar papers or presentations, it is much less clear how to grade them. In my opinion, due to the lack of a sample solution as clear reference, the whole grading process easily becomes quite subjective: Grades are given more based on a gut feeling rather than due to the fulfillment of objective criteria. While this approach may be acceptable if said gut feeling is reliable enough, it certainly poses a problem if you do not have enough grading experience to have developed a good intuition about grading.

Another issue that is in my opinion important especially with respect to seminar papers is the lack of feedback given to students. Since the grade is given based on a general impression (which may be difficult to justify and defend), it is very tempting to only inform the students about their grades without giving them some feedback on what was good and what could still be improved about the paper they handed in. However, such explicit feedback is in my opinion crucial for the overall learning process: If I’m never told as a student that my sentences are too long and that I need to use more citations to support my claims, how can I learn to improve with respect to these aspects? And if I’m never told that my diagrams are great, I might continue worrying about optimizing them further, since I’m afraid they are not good enough.

The Solution: Grading Sheets

For my own teaching, I have found grading sheets to be a very useful tool for improving my grading process. But what exactly is a grading sheet?

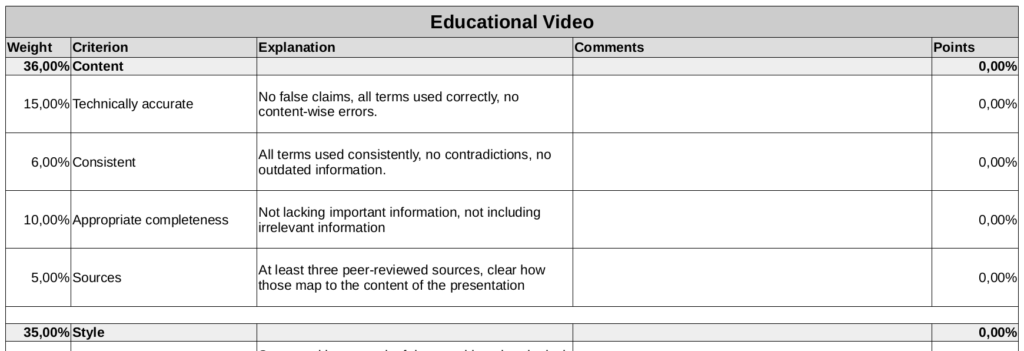

A grading sheet is essentially just a list of criteria (possibly grouped based on common aspects) that are weighted by their relative importance. For instance, in my current seminar, students have to create an educational video. When grading this video, I have decided that the content makes up 36% of the grade, while style is responsible for 35% of the overall grade. 14% are determined by the technical quality and 15% by questions that the students have to prepare for their own video and that other students need to answer. In each of these categories, there are different sub-criteria which are accompanied by a short description. For example, the technical quality is split up into audio quality (Speaker can be heard loud and clear, appropriate speed of talking, no noise or distracting background) and video quality (Appropriate resolution, text and images good to read/see, no typos and grammatical errors in text, clear and free from distractions) with a weight of 7% each. Figure 1 shows an excerpt from this grading sheet for illustration.

When using such a grading sheet to determine the overall grade, I give points for each of the individual criteria (usually on a 0-100% scale with steps of 25%). Moreover, I try to write a short comment with respect to each criterion that justifies my assessment and that hopefully helps students to improve in the future. The overall grade is then computed by a weighted average of the individual ratings.

What are the benefits of this approach? First of all, it helps me to grade papers and other deliverables in a more structured way. While I still have an overall impression of the work, the grading sheet forces me to look at the same specific aspects for all students. This also ensures that the resulting grades are comparable. Moreover, since I design the grading sheet ahead of time, I can share it with my students before they hand in their deliverables. This makes it clear from the beginning which aspects are important to me when determining the grade. By checking the grading sheet before submission, students can make sure that they didn’t miss anything important. Finally, I am able to give specific feedback to the students, simply by sending them the filled-in grading sheet. This makes the grading process more transparent and hopefully provides them with useful pointers for future improvements.

Pitfalls: Level of Detail and Balance of Aspects

Creating such a grading sheet obviously requires some time. After all, you need to think about all aspects that should influence the grade and then put them together in a structured way. However, once you have done that two or three times, you are in my experience often able to recycle parts of old grading sheets when deriving a new one. The amount of time needed to invest thus is usually not a big concern. However, there are also some things that you can do wrong and which you should of course avoid when creating a grading sheet.

First of all, you should make sure that the different high-level aspects are reasonably balanced. In a seminar paper, it is for example very easy to come up with many criteria that are based on formal requirements (page limit respected, tables properly formatted, no typos, references according to expected format, etc.). On the other hand, it is often more difficult to nail down specific criteria for the content of the paper. One may thus be in danger of putting to much weight on formal criteria while not reflecting criteria about the content in an appropriate way. This can be counteracted by the category weights to some degree, but if one category (e.g., “content”) only consists of a single, very vague criterion (“content is correct and well presented”), this is not very helpful for objectivity and feedback.

A second potential pitfall concerns the level of detail: In my first grading sheet I had 72 criteria with respect to the seminar paper, 39 criteria for the presentation, and 8 criteria for the peer reviews we wrote as part of a simulated conference. In total, there were 119 criteria to be assessed for a single student! This was clearly too much and I was barely able to see the forest for the trees. For instance, the presentations were barely long enough to allow me to go through the whole list of presentation-related criteria. Moreover, I was not able to give meaningful feedback to most of the individual points. I have therefore moved to less fine-grained criteria with a larger amount of textual feedback for each of them. In my current seminar, I am down to 20 criteria, which is much more manageable.

Another issue related to the level of detail is the “resolution” of the grading scale for the individual criteria. I mentioned above that I use the five-point scale 0% – 25% – 50% – 75% – 100%. In theory, one could use the full scale and for instance give 87% on one criterion, or 13% on another criterion. However, this makes the grading process painfully slow – plus usually, you can only make a relatively rough judgement and using a 100-point scale only gives an illusion of precision. I’ve found the five-point scale to work quite well for me, since I can interpret the five stages as “not fulfilled at all” – “barely fulfilled” – “on the border of passing” – “good, but minor shortcomings” – “negligible shortcomings”.

Overall, I think that grading sheets are a good tool for grading “unstructured” exams such as seminar papers, presentations, and posters since they provide you with a clear structure and allow you to give structured feedback to the students. And as far as I can tell, the overall grades coming out of such a grading sheet reflect my intuitive gut feeling quite well.